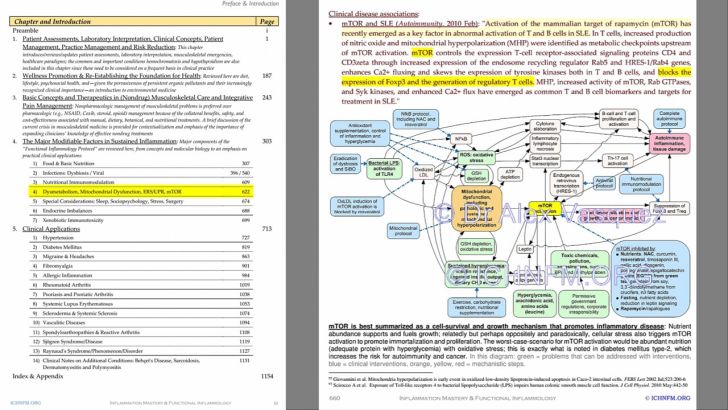

Contents:

ICHNFM 2013

Context—I got my groove (videos) back

Censorship and “prebunking” in the age of the Plandemic “new normal”

Related videos and links

VIDEO TRANSCRIPT (unedited)

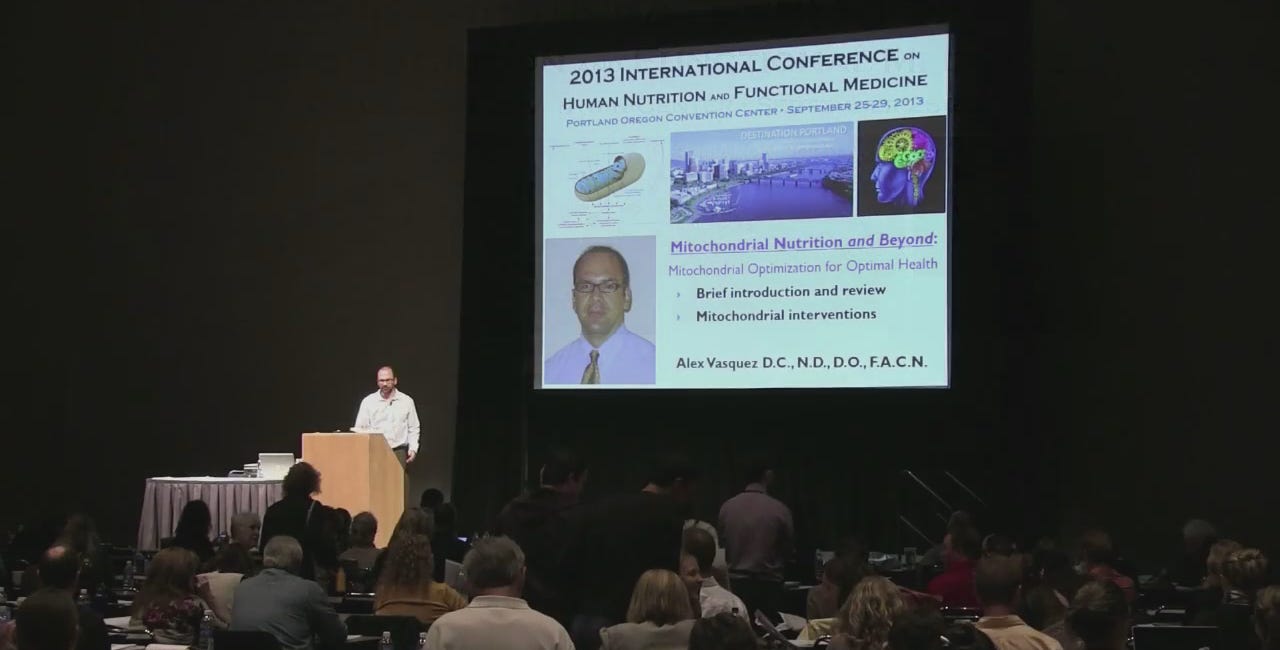

ICHNFM 2013

ICHNFM simultaneously represented International College of Human Nutrition and Functional Medicine and International Conference on Human Nutrition and Functional Medicine, both of which were organized solely by Dr Vasquez for the benefit of his graduate students and specifically the need to host a world-class conference. The mission was completely accomplished but at great personal cost to DrV—the process of single-handedly organizing a post-graduate and graduate conference was nearly lethal, especially while combating a world of academic corruption.

Context: I recently regained access to one of my online video archives (built over the past 12 years) that for whatever unclear reason had slipped out of my control even though I’d not changed any contacts or passwords. Some of the videos were being deleted without reason…unless we consider Covid censorship and “prebunking” to be a reason within “the new normal.”

By now in 2025—almost exactly 5 years from the start of the plandemic and its concomitant censorship—those of us who are alive to read this have survived 5 years of global censorship of ideas, expertise and perspectives.

“Prebunking, defined as “the process of debunking lies, tactics, or sources before they strike”, didn’t exist in common parlance before the Covid Plandemic, when it suddenly became a tool to control ideas, censor experts and maintain social control during the biggest medical-political fraud to occur in the history of humanity.

During the Covid Plandemic, censorship became an integral part of “the new normal” whereby no-one could safely speak out about antiviral nutrition, the dangers of fast-tracked vaccines, or any perspective—specific or not to the plandemic—that demonstrated expertise on any topic whatsoever. The latter was a strategy dubbed “prebunking” whereby experts on any topic such as research or pathology or epidemiology were attacked even before they might have thought of anything to say against the plandemic so that when and if they ever dared to speak-up then their expertise would have already been undermined and thereby their comments would theoretically have no merit in the eyes of the brainwashed masses comprising a clear majority (ie, ~80%) of the population.

“Prebunking, defined as “the process of debunking lies, tactics, or sources before they strike”, didn’t exist in common parlance before the Covid Plandemic, when it suddenly became a tool to control ideas, censor experts and maintain social control during the biggest medical-political fraud to occur in the history of humanity. In the United States, the public-funded National Public Radio (NPR) has been on of the biggest sources of pro-pharma anti-nutrition anti-autonomy medical misinformation, so of course they pushed the “prebunking” narrative as a technique of virtue signalling (ie, “you can trust us but you can’t trust anyone else”) while they themselves are guilty of misleading millions of people away from accurate information and into the propaganda labrynth of drug infomercials, such as the ones I have reviewed below:

I WILL BE RELOCATING THE PREVIOUS VIDEO ARCHIVE TO THIS [SUBSTACK] PLATFORM: I recently regained access to one of my online video archives (built over the past 12 years) that for whatever unclear reason had slipped out of my control even though I’d not changed any contacts or passwords. Some of the videos were being deleted without reason…unless we consider Covid censorship and “prebunking” to be a reason within “the new normal.”

CONFERENCE VIDEO Integrating Functional and Naturopathic Medicine (F.I.N.D.S.E.X.® Protocol) into Medical Practice for Common Primary Care and Specialty Conditions [2020, Moscow]

This presentation was scheduled to be delivered physically in Moscow in 2020, but obviously the globalists had other plans for us and international travel was canceled during the European lockdown.

Vasquez, Mitochondrial Nutrition ICHNFM2013 Presentation

SUBSCRIBE to access the entire archive of articles and videos including the “goldmine” series on Vitamin D in 1) chronic pain, 2) mood/depression, neuroinflammation and neuroprotection, 3) barrier defense, 4) inflammation/coagulation and immunomodulation

*UNEDITED* VIDEO TRANSCRIPT

Microbiology doesn't exist separate from psychology and sociology. Because we know that when we're stressed out, when we're susceptible to microbes, so our social climate affects microbial balances, and we'll talk about that later today. So I think functional medicine allows those different disciplines to intersect, and obviously we use that clinically as a tool.

So again, honoring Dr. Bland’s contribution to the broad discipline of health sciences, not simply for adding to existing science, but more so for adding new grants on the tree of science. Obviously, many people have contributed to this. I'll show you in a moment the functional medicine matrix, which is certainly our clinical application of functional medicine,

but also represents the work of many, many people,

many focus groups, many conversations, thousands of emails, and different conversations in that regard. So again, With the appreciation that I think Dr. Bland served as the nucleus for this idea, also appreciating the contribution that other people made to it, I still want to go back to honoring Dr.

Bland because I think every idea and every movement needs a leader. It has to have some nucleus around which the other components can form, kind of a scaffolding.

And I talk about that in a few more slides, but I'll just read what I wrote here. Every great idea and movement needs a person to guide and nurture. to serve as the nucleus around which others can build structure and add conceptual and intellectual scaffolding, which, while the result may be a group effort,

was certainly initiated by one of them. And as many of you know, Dr. Bland itself comes from a pretty rich heritage of how to work with Dr. Pauling. And as most of you know, Dr. Pauling was who originated the idea of molecular medicine with his discovery of the amino acid substitution in sickle cell and human.

Microbiology doesn't exist separate from psychology and sociology. Because we know that when we're stressed out, when we're susceptible to microbes, so our social climate affects microbial balances, and we'll talk about that later today. So I think functional medicine allows those different disciplines to intersect, and obviously we use that clinically as a tool.

So again, honoring Dr. Lamb's contribution to the broad discipline of health sciences, not simply for adding to existing science, but more so for adding new grants on the tree of science. Obviously, many people have contributed to this. I'll show you in a moment the functional medicine matrix, which is certainly our clinical application of functional medicine,

but also represents the work of many, many people,

many focus groups, many conversations, thousands of emails, and different conversations in that regard. So again, With the appreciation that I think Dr. Bland served as the nucleus for this idea, also appreciating the contribution that other people made to it, I still want to go back to honoring Dr.

Bland because I think every idea and every movement needs a leader. It has to have some nucleus around which the other components can form, kind of a scaffolding.

And I talk about that in a few more slides, but I'll just read what I wrote here. Every great idea and movement needs a person to guide and nurture. to serve as the nucleus around which others can build structure and add conceptual and intellectual scaffolding, which, while the result may be a group effort,

was certainly initiated by one of them. And as many of you know, Dr. Bland itself comes from a pretty rich heritage of how to work with Dr. Pauling. And as most of you know, Dr. Pauling was who originated the idea of molecular medicine with his discovery of the amino acid substitution in sickle cell and human.

really where our heritage began, also obviously with Roger J. Williams,

obviously before that, and many others. So one of the ways that we apply functional medicine model, and whether we use that as a specific tool or whether we use it just as a

conceptual background, what it allows us to do is form a schema behavior. And as many of you know, Nietzsche is my favorite philosopher, so I always like to applaud his work. So one of my favorite quotes from Nietzsche is, In order for a particular species to maintain itself and increase its power,

and the power in this context just could mean clinical effectiveness, for example,

its conception of reality must comprehend enough of the calculable and constant for it to base a scheme of behavior on it. And I think that's what we have with the functional medicine matrix and the

functional medicine application. It gives us a scheme of behavior. It gives us a way of understanding how things work together. So we can use that then as an intellectual checklist and make sure that we've covered all of the most important pieces

Now, even in this model, we could probably identify things that aren't included, that should be included. But I think for this model to be clinically applicable,

it has to be functional and therefore must be somewhat limited so that we're not overwhelmed with 10,000 data points and a 10-minute visit. So this model certainly covers the biggest basis. And again, I think that provides us a clinical framework and a scheme that we can move forward with when we work with patients, but also,

as I said, for understanding even how basic sciences can interrelate with each other. Again, going back to the example of microbiology, which will be one of my themes throughout my first presentation, certainly in the last presentation of the day, you're going to see how microbes really affect inflammatory balance.

But the question then becomes, well, what affects microbial balance?

If microbial balance affects immune balance, what was before that? Diet, sociology, culture.

So Dr. Gland has been my professor and mentor for the last about 20 years. When I first started listening to his audio tapes from the library, those tapes were nutritional biochemistry. And that was a series of seminars and talks that Dr. Gland had put together many, many years ago, back in the 80s,

I believe, if not 70s. And back in the day, we just recorded the lectures, and of course, I dubbed them so I had my own library. And so in that sense, Even before we met personally, Dr. Gland was kind of my intellectual mentor with regard to nutrition and what is now

functional medicine. Here I am caught guilty drinking a Coke when I was a kid. I left my other siblings out, but I didn't mind sacrificing my brother. I'd like to say that that was the last soft drink I ever had,

but it wasn't because obviously we had to mature in our understanding of what's healthy and what's not. I'm sure you all remember the ads from back in the 70s and 80s, right? Coke adds life, right? None of us would say that now. But back in the day, that's the model that we grew up with,

that certain foods were consistent with a healthy life. Obviously, again, none of us would agree with that.

Part of the reason I put this slide in here is because even though I'm caught guilty with a Coke in my hand, or suffering of some sort, I actually started studying nutrition even when I was very, very young as a kid. Back in the 70s, my dad was one of the so-called health nuts,

which meant he exercised and tried to get a healthy diet. That made him a health nut back in the 70s.

But I grew up being exposed to his ideas and cod liver oil, which we had to have for breakfast when I was with him, vitamins.

But it didn't serve simply as a dietary pattern necessarily for me. Here I am, guilty. But what it served for me was to start planting seeds of questions. And so I remember, even as a child, my dad would say, well, we have to eat healthy, or you can't drink water with your meals,

or you have to take hot liver oil. And even though, of course, we didn't understand things back then, but we couldn't the level that we do now, it just started seeding these questions in my mind. Why do some people eat the way they do?

What's the benefit of this pattern versus that? Why are some people concerned about that and other people are indifferent to that? So even as a young man, young boy, I was aware of nutrition. I started studying nutrition when I was a teenager and later went on to kind of really enjoy science, molecular biology,

and move forward through different programs. I was starting with chiropractic because I was interested in exercise. manual medicine, nutrition, then going to naturopathic medical school to further my education in nutrition and botanical medicines. And then later, after a couple years of clinical practice, going to osteopathic medical school.

And I loved it then, and I still love it.

This is one of the tapes I used to listen to. And I can actually quote this, I can actually quote Jeff Blant back to himself. I've listened to this tape so many times.

But again, as you can tell from this tape, this was actually, the date's not on this, but this was Advanced Clinical Nutrition 1994.

And a couple of times I've told Jeff, I said, you know, your ideas back in 1994 still haven't been incorporated into medical schools. Because one of the things he said in this presentation He said, one day, biochemistry is not going to simply be a flaming hoop that medical students have to jump through.

It's going to be a clinically relevant course. And we're way past that time. It should have happened. And I don't know that it's happened yet. And I would say it probably hasn't, but certainly not to the level that we're going to discuss today. So again, honoring him for being such a pioneer.

This was back in 1994 again, so about 20 years ago. And what he says back 20 years ago is still relevant today, it's still accurate today, and it's still cutting edge compared to, I would say, the majority of healthcare. So again, recognizing Dr. Gland, not simply for adding to an existing tree or branch,

but adding an entirely new branch onto the tree of science. So, we have an award for Dr. Gland, which I'll be happy to... Co-deliver with Deanna Manage in just a moment.

So what this award means for me and why Deanna and I selected this, at least for me, what it represents is force. Because all of this takes massive effort, not just a little bit of effort,

but a lot of hours of work until 3 o'clock in the morning. And I think this also represents grace, danger, flow, also leadership, but also teamwork. You can see that one whale is slightly ahead of the other. And he's pushing that force current ahead of himself even still, right?

So that's why we selected this trophy. People who contributed to this,

myself, Deanna Minich, several of our students, Andrea, Jerry,

Paulette, Monica, Terry, Joseph, Kathy, Francis, Sandra, Paulette, Ryan, Karen, George,

Eric, Georgia, Karen, Angeli, and So I think at this time, we'll deliver that award to that plan. So this is on behalf of your students, all of us who are your students, and even your students' progeny.

All of those who benefit from your work and the teamwork of the functional medicine legacy. On behalf of the International College of Human Nutrition and Functional Medicine, thank you for your contribution to science, basic science, as well as science.

Just to take a moment to collect myself here. I think,

first of all, what can I say other than the deepest,

most authentic and emotional thank you for the acknowledgement of what has been a really remarkable and unexpected path for me over the last 35 years. To have people like you who are doing more than I would have ever dreamed were possible as affiliates is the greatest compliment I've ever had. I think you all know as teachers,

you evaluate your role as a teacher when your students are better than you.

And I've been very blessed to have students that are better than I am. So, thank you so much.

Another interesting little fact for you, and I'm not going to tread a little bit on the humor going through the series. My son, Kelly, is 44.

My oldest son, I have three boys.

And so he texted me last night and said, well, Dad, you're out here in Portland. I said, yes. And he said, well, how's it going? And I said, I'm having an unbelievable day-to-day experience because my journey in this whole field started in Oregon. Some of you know that I went to graduate school and then

to Oregon Health Sciences in the medical school back in, yes, it was the 60s. And I did have the long, bushy woodsman red hair, the big red beard, the little eye stuck down inside the bushy mane of the bear from the Northwoods. My family, which lived at the time in Southern California when I would come home,

couldn't believe that I had been born as the Northwest woodsman. But the,

The hotel that I'm staying at tonight was the first real hotel as a junior assistant professor when I took my first real job at the University of Utah in Washington, finishing up here in Oregon. And in 1970, I started with my first research,

who went on to become the head of internal medicine at John Hopkins many years later. But Phil came to me and said, I want to do some research in vitamin D.

And I did nothing, really, about what I mean, other than Alex and I shared a similar thing with our family. My mother, in this case, was the health deputy, and we were raised on Dale Davis, and we never had white bread or desserts or soft drinks or sugar.

And my mom and dad were in constant battle because my dad was kind of a Midwest

traditionalist about nutrition, but my mother would never let us be so exposed in my father's poor ways in terms of nutrition selection. We would always go, and I'm also, interestingly enough, connected to Deanna Minnick in this way because we, as kids, would be sent to school with, we couldn't eat the cafeteria lunches, obviously, at our elementary schools.

We had to go with the bag lunches of, you know, the cut vegetables and all these various whole grain things. And we were, you know, both she and I have commented, we were expunged by our fellow students, you know, thinking, what were we being subjected to cruel and unusual punishment?

Didn't our mothers know how to really give us good lunches? And so we felt like we were discriminated against. It builds a tough spirit over the years and you have to be the outlier.

So when I arrived here after completing my work in Oregon and then went up to Puget

Sound and had Mr.

Madden become my first research student, we were very lucky that our research actually was very successful and it got a lot of motorized. We were the first group to actually discover the co-collectual mechanism of the action by me in protecting membranes

against oxidative injury. We published these papers and suddenly people were calling me a nutritionist, which I always wondered who they were talking about. And I recognize they were talking about me because I was working on something that had to do with nutrition. I was a nutritionist.

And at first I thought it was very strange, then later I really wore this with great pride. I thought, wow, this is pretty neat. I got a degree in an accreditation and I already went to school for it. This is pretty neat.

And so my first opportunity then to come back and speak to doctors about this work as kind of this nutrition guy, this nutritional biochemist, was 1973. in which the hotel that I stayed was the hotel I stayed in last night. And so this was like an unbelievable back to the future, 360 for me.

And I remind myself that yes, it's been, so that was 73, so that was 40 years ago, right, by my math. that everything changes in 40 years and nothing changes. So that's the holography of life, right? And there's a really powerful metaphor about that because we live every moment in every other moment of our life.

And sometimes it's heartbreaking, including our futures, I believe.

So it's not just our present and our past, it's also our future, because we're creating our future in the present, in the trajectory of all of our lives. What is the lesson plan? What's the journey we were on? How does that kind of direct us, in my case,

to do 360 over 40 years and end up in the same hotel, possibly even in the same room,

except with a little bit more knowledge, and a whole lot more joy, because I kind of understand the journey a little bit better now,

40 years, than I did when I was at my first medical meeting, was trying to go over my slides, and dropped on the ground, I recall, and this is back when there was slide projectors, you know, projectors, and I was so nervous,

I dropped my slides,

and then tried to put it back in order, and then put it in the right order, and somewhere upside down,

I winged it. So nothing has changed. It's all kind of like the same. Circumstances are a little more high-tech now. This is an incredible privilege to share this moment with you and to be honored and

taken with very, very deep humbrage because it is, as Alex said,

a collection of extraordinarily dedicated individuals that have allowed us to arrive at this place where we can start to actually have some voice. And I don't want to over be able to exaggerate,

but we're starting to have a voice in this concept of functional medicine had a larger theater of impact in policy making and decision making. There are functionalistic programs that are now being started with the VA with

returning vets back then. We're coming back with all sorts of functional injuries, both emotional and physiological and physical. And we're starting to have an impact at various medical schools. medical schools that have a use of our textbook of functional medicine. And we're starting to have an impact on large clinics.

There are now discussions about collaborative projects with major,

and probably shouldn't disclose,

but let's say some of the most visible iconic names in medical clinics in the United States want to help functional medicine programs.

So it's starting to get some traction. And it's a consequence of the tireless work and the dedication to excellence that

all of you and people like Alex and Rob that we even have that chance. to have that dialogue. So I'd like to take this moment and turn the table around for a moment because, as I said, every good teacher really honors and celebrates their students. And Diana,

maybe you can step up here and maybe you can take a moment to acknowledge a special person.

Yes, definitely. So Dr. Glenn and I would like to take this time to acknowledge Dr. Vasquez with an achievement award. And before I go into reading his long list of achievements, which many of you are probably already familiar with and have even been a part of,

I'd like to just say that it's been a pleasure working with Atlas this year. I had the opportunity to work with him as part of the faculty for the University of Western States co-teaching. So that was a great experience. and then watching him almost single-handedly go through this process of creating this conference,

this international venue of information and inspiration. So he is quite remarkable. It's not common that you see a tried-degree person handling not just creating a whole new degree, but also a conference, writing books, and really forging them around. So just to, for those of you who aren't as familiar with Dr. Vasquez's background,

He served as the founding program director for the Master of Science degree program at Human Nutrition and Functional Medicine at the University of Western States. He's brought a wealth of clinical experience, scientific knowledge, administrative skills, interprofessional contacts and partnerships to the university. I think that's the beauty of his background,

that he can meld the science so beautifully together with his clinical experience. He is the world's only clinician, researcher, and professor-author to have achieved three doctorate degrees in three different healthcare professions, and is the author of 15 books, and I think we even have four books coming out next year, right? So let's make that almost 19.

And more than 100 scientific articles. He's here in the respect of students, physicians, and other health science professionals worldwide. He also, I would like to make mention that he recently founded not just having a master's program and this conference, but also a journal. the International Journal of Human Nutrition and Functional Medicine, which is a platform for students,

faculty, and other clinicians and researchers to rapidly and broadly publish their works at no cost to themselves or their institutions. What I really like about Dr. Vasquez is that he sees the need, what's not working in different systems, and goes beyond and recreates them.

He was an honor student at the University of Western States and also at the University of North Texas Health Science Center. He completed a pre-doctoral research fellowship sponsored by the National Institute of Health. He is preeminent in his knowledge of basic and clinical sciences. And I'll end by saying that not only is Dr.

Vasquez an incredibly brilliant scientific researcher and very skilled clinician, But he's very well-rounded. He is not just left brain, he's also right brain. And as he mentioned with his quotes, he has a lot of love for the fields of philosophy, psychology, as well as politics and organizational leadership.

So it's not very often that we find such a well-rounded individual who has contributed so much to science and especially functional medicine. So with that, Dr. Brent and I would like to present Dr. Ekman-Vasquez with the award.

So as you probably all know, Dr. Bennett is Vice President of Education for our new organization called Personalized

Environmental Medicine Institute, and I'll say a few more words about it later. And we both were very, very privileged to have this opportunity in a formal way to acknowledge Dr. Vesquez, who has been a friend and colleague for, as he said, for his 20 years of mine personally, a person that I've admired and watched his career grow.

And so this is an achievement for Alex Vesquez, and the KLM I would like to provide you. And it says, the Personalized Lifetime Medicine Institute honors Alex Vesquez for a significant contribution to the global revolution of health care through its leadership in medical education and clinical innovation over the past 20 years.

His commitment to clinical excellence and systems-based medicine served as

standards for medicine in the 21st century.

Awarded September 25, 2013, we're very proud to honor you. I appreciate that. And this, by the way, was totally spontaneous. This was going to happen like five minutes before we came on the stage, practically. So, I appreciate that. It's probably not much more.

Well, you know me, there's always something to be sent, so let me fill a couple of minutes here. I thought maybe what I could do with the main time is to talk about the evolution

of an idea to the clinical practice, which is this functional medicine model. And just for those of you that are unfamiliar with its origin or what it really means, I'd like to spend maybe 15 minutes to kind of give you a quick,

compressed review of how this all came about. And I think someone said, actually David said it to me just before we came up on stage, and he said, you know, it's not very often that you can take a term and reframe it to have a whole totally

different meaning when everybody thinks they already know the term. So in 1989, my wife, Susan,

my dearly beloved partner, who had been the vice president of the organization that I've been involved with at HealthCom, which is our company, said to me, you know, Jeff, you travel about five million miles around the world as kind of this ambassador for nutritional chemistry and clinical nutrition and so forth. and you probably traveled a lot,

maybe more than you needed to, and maybe we could form an institute and people could come here to learn.

You know, would that be an interesting idea? And I said, well, you know, we really don't need another institute. I mean, there's like all these organizations and it's a proliferation of organizations. He said, well, no, you're going to think about this. I'm telling you, it's a little different than all these other organizations.

Not that these organizations are bad or wrong or doing the wrong thing, but maybe you could codify these concepts. And I said, well, before I would even consider that,

I think we should ask, what is the novelty of our idea? What is the uniqueness? How does it differentiate itself? So she came up with the idea.

And let's sponsor, and this was 1989-90, a meeting where we'll bring thought leaders in. We'll pay for them to come in.

And she shows Victoria, British Columbia, a nice little spot. And we'll spend three days with a whiteboard and just talk about what it is.

would be the best of all worlds if we could create a health care paradigm shift that would add value and reduce upbringing and improve outcome. And so we, you know, I had the privilege of all these miles of travel meeting, all these very remarkable thinkers from different disciplines.

So I kind of hand-picked about 20 colleagues that represent all sorts of different disciplines. It really isn't necessarily from no one. And we threw them together in Victoria with a whiteboard with this broad objective. Let's just talk, open-ended. All ideas are open for discussion about what the ways of what mental health care

could look like if it was idealized.

And it turned out to be an extraordinary and robust and intellectually stimulating three days. I mean, it was just amazing the ideas that percolated.

And out of that, I recall on the second day of this discussion and thinking about this, and I'm going to get some precedent saying, or some precedent saying, that I had in a one and two, taken as a bath of the Pauling Institute,

where I was the head of nutritional research for Linus Pauling for a couple of years down in Palo Alto, Stanford. So I had already been infected with this idea that Alex said they're talking about as it relates to molecular medicine, about molecular medicine.

And of course, my training coming up through the point about chemistry, I was already kind of prepared for the chance of discovery. So when we had this discussion in Victoria, I did If you recall the second day, waking up, actually, in the middle of this is almost like teculite with the monkeys swirling in his mind,

I woke up in the middle of the night and I said, I think this is all about function that we're talking about.

Because function goes into dysfunction, which precedes pathophysiology. So maybe we should back this whole model up,

because function is a unifying theme, I believe, that all disciplines are interested in some level, no matter subspecialties or or exercise physiology or psychology or whatever it might be, whatever the discipline. It seemed like function was an operative term. But the problem was that function, as you know,

in medicine really had two kind of already preceded meanings. One was psychosomatic illness, functional illness, which really is another way of saying that person has a problem in their mind is a psychosomatic illness.

And the other was the geriatric medicine functioned at,

you know, orthopedic problems or gait disturbances or inability to have activities that they were living. So it had already these kind of undercurrents of precedent of the term functional medicine that would be different in the way that I was defining it. But when I went to... To the PubMed, this was really pre-internet PubMed,

and I kind of went to the library of medicine and did a search as to how functional

medicine was being used. The word function, I did find there was some early stage, even back in this would be 1990, in radiology, we started to see the development of functional radiological technologies like functional MRI.

So I said, hey, maybe people are kind of reframing this term. And then I got this idea, which is a little cute,

but actually I really was true, and I've said this many times, and I said this to the group when we came back in 1990 to read the same group, back to Victoria the second year, I proposed, as I said, if you think of the term functional medicine,

let's say that we have a thousand health practitioners in an audience that ran across all sorts of different disciplines. And then we asked how many of them would affiliate with the term like holistic or alternative or unconventional or molecular or all the various terms that were out there,

integrative, whatever it would be. There would always be criticism of some term. And so I said, okay, now let's say if I ask How many people would like to practice dysfunctional medicine? Probably no one would stand up and be counted. So my thought was that everyone would want to be affiliated with functional medicine, right?

They would want to think of themselves as a functional medicine practitioner.

If we just got that as a mind space, like a virus in your central nervous system, now we can infect that, right? So that was the concept. So let's find a term that everybody would have difficulty criticizing.

and then redefine it so it becomes a positive part of their belief system. So that was the start of the term functional medicine in 1990,

and we re-framed in the same group of violators. And then we made a decision, and this was, Dr. Alex and I share a common similar phenomenon, we made the decision to have our current meeting of what I

I guess boldly said it was going to be the Institute for Functional Medicine, which was going to be in the spring of 1991.

And we chose a place that we thought everyone would want to go, so we chose Hawaii. Now, when I chose Hawaii as the first place, and my lovely wife Susan, who's extraordinarily good at these types of logistics then,

said, well, where can we be? And I said, why don't we go to the Four Seasons? Now, I had never stepped foot in the Four Seasons, the constant moves there per night were like,

and she said, well, you know, come on, be reasonable. I said, well, you're a magic maker.

Let's find a way to see what we can do for the Four Seasons. So when I think back to this, it's hilarious because she negotiated $129 rumorings at the Four Seasons on the White Bay. now including those that have been over to Wailea and Maui you probably know that

that's just hard to even believe we got these 129 and people if they upgraded to CPU rooms they got 149 so so we ended up being here for a week at this incredible

And we actually found enough sponsors that when we signed a contract, no one was going to come. We had suddenly $150,000 of overhanging that we were responsible for that we would have soon looked at one another and said, well, this is going to be off in new pockets if no one comes. So we did it.

I think we almost broke even. We broke even on that meeting. And that was the start of the formality of the Institute for Culture Investment. And it was a remarkable group of individuals, a lot of whom, by the way, were practicing for Oregon in that initial group.

We had about 200, I think, a little more than 200 attendees,

and I think in state representation, naturopathy in Oregon was one of the principal disciplines that was at our first meeting. And the concept that we said is we're not going to discriminate functional medicine among degrees. We were going to discriminate only in one way about excellence of commitment.

And so we wanted to get to the brightest and we weren't going to be embarrassed or

apologetic if it sounded like we were being a little discriminatory because we wanted people who were really committed to learning, really committed to asking the right questions and really committed to the discomfort often of saying we don't know enough and we've got to pursue knowing more. And so our theme was we don't discriminate on degrees,

we discriminate on commitment to excellence. And I think that's played out pretty well over the last 23 years or 22 years since IFM was first formed as an institution.

Then, as you probably know, it was the second international conference, which was in MacGyber, British Columbia. We then started the Lions Falling Award for Function Medicine, which I've been extraordinarily proud to see now be able to honor.

People not only inside the House of Function Medicine, but outside who really don't even know if they're contributors to the medical paradigm until they come to our meeting and they say, wow, I didn't even know what was going on around me. So this is how I think ideas start with great people and they germinate up and they

refine and they mature and they kind of morph into something much bigger than you would ever expect. Now, why did we do this? And I think the answers are pretty clear.

This audience seems very well informed. I don't need to go through this other than the fact that the statistics right now today, 2013, about what's going on in healthcare are very alarming because this rising tide of the birth of chronic disease is bringing economies to their needs.

And these are the kind of social forces that can actually so disrupt economies that it can changed civilization. When you have a rising tide of chronic illness in which your younger people are getting diseases of the old,

and your older people are being kept together by metal iron bubblegum so that they're still consumers, but they're medical consumers and they're not productive consumers, you've got both ends of the continuum that are pushing to the middle to disaster. Because you have fewer people making incomes that are healthy that can support the people that are sick.

And you've got sick people on both sides of the Gaussian curve. So this is what's going on right now as we see the rising tide of type 2 diabetes and arthritis and coronary disease in younger people that were fairly... 20 years ago. And then, of course, overage individuals that were pushing with modern technology,

keeping people alive by hospitalization and high technology intervention, these high utilizers. of medical services. These are like the worst case scenarios on both sides of the house. So we have a big problem. And in fact, when I looked at the overhang of Medicare for individuals who were the early baby

boomers who are now on Medicare moving into the next 20 years, that overhang for Medicare services to provide services equivalent to today, not even projecting ahead, is equivalent to 3.7 times the national level. It's sometimes $35 billion.

And I can't even get my hand around that number, quite honestly.

What it just says is it's gargantuan exposure to economic need. So what's going to happen? We don't have that money. We've already kind of leveraged that money and sold it out. So what are we going to do? We either have to go to ration care, or we have to go to suboptimal care,

or we have to go to those that are going to afford and get the resident that will get behind those. Or we have to change the system, right?

And so that's the force, that's the great force of change. Because the only logical humanistic, compassionate, and economically viable approach is the higher approach. We have to change the system. Now the question is, well, what does that mean? And as Mark Hyman said, we have to change not only the medicine we do,

but how we do medicine, right? This whole system has to be changed, not just kind of manicuring who has access, to a crisis care system.

That's important when you have universal access, but access to what? And so I think we're in that phase right now in which functional medicine, as a concept, has an opportunity to be voiced in this dialogue because it is one approach using the systems biology thinking for chronic disease.

In 2009, the World Economic Forum posed that chronic disease is the most severe threat to global economic development. And everything, you might say, well, how about environmental despoilation? Well, actually, environmental despoilation is pretty closely affiliated with rising epidemic of chronic disease. Those of you who have traveled to Beijing or Shanghai, you probably know what I'm talking about.

You can't even live there for a day without getting respiratory problems. I mean, you've got such a connection between pollution and disease. It's hard to separate out one and say, well, I'm an environmental scientist. No, I'm a medical person. I mean, it's all interrelated. The water, the air, the food.

When you start getting melamine in food, you start saying, what the heck is going on here?

What's our mindset about the survivability of this fairly frail species that we call a human that doesn't have a large litter size? They're not that strong with the body. They don't run that fast. They don't have protective coloration. They have to use their unique spinal tumor called the brain to survive, and they're putting that to sleep.

So these are the kind of challenges that I think we're confronting for which functional medicine has one voice in this dialogue. So the old model doesn't work because this concept of one disease caused by one agent for which we have one pill, that would be like pneumococcus producing pneumonia for which we have one antibiotic.

That's a nice linear model. By the way, you can kind of learn and generalize that in about three days in school. Every disease is that simple. One agent produces one disease for which one drug treats it. Wow, wouldn't that be marvelous? But the problem with these chronic diseases is that they're very complex.

And as someone said to me the other day, I was at this meeting with world leaders in diabetes research. And the first time I got up and spoke, right before Bruce Spiegelman at Harvard, who was respected as being one of the top resident researchers in infecting diabetes, the preceding speaker was the head of endocrinology at Mass General.

said, you know, if you have 100 type 2 diabetes patients, you have 100 type 2 diabetes patients. No two patients are identical. That every one of those diabetic patients has a slightly different disease. We lump them together for ICD-9 convenience and ability, but actually in terms of how they should be managed, they're uniquely different.

And that's why you do this whole portfolio of drugs. It creates good ideas. Because with one disease, maybe just one drug would work. But, you know, you've got to mix and match and move around. And as you probably know,

we still don't have all the remedies in the pharmacology that blow back to manage this complex condition. Because it's really a condition that's associated with metabolic disturbance that comes as a result of a mismatch between genes and the environment. And that's what I just said very quickly,

and I repeated that in front of the mirror many thousands of times.

That's a paradigm-shifting concept. I said it without a motion, kind of just very flat.

But if you think about what I just said, it is an absolutely paradigm-shifting concept.

And that is that disease, as we know it, really mechanistically emerges from the intersection between a person's lifestyle and environment with their genes.

The outcome of that, called gene expression, is what we term for eating as a disease. There is no such thing as a disease in the purest sense of the abstract. A disease is the body's response to a mismatch between its genes and its environment.

Now think about that for a moment. And you say, well, look, is that really true? What about our friends? Or what about VRT?

Or what about, let me just choose a disease of the month, whatever you would like. What about the mission? Are you saying that all these conditions are really a consequence of a unique relationship with that person's genotype? and epigenotype to their environment. And that's what I'm saying.

That disease is the outward manifestation of the histopathology that results from a process of altering function over time from a body's response to its environment in a way that it probably should. It's programmed to do that. The problem is when you put the pedal to the metal for a long period of time,

you get what's called collateral damage. That's called disease. You get where I'm going here? So it's taking our knowledge base. I haven't shifted our knowledge base. I haven't said, let's go to a whole new system of anatomy and physiology to explain it. I've said, take the same data set,

the same system of anatomy and physiology that we describe in school, but let's frame shift how we see that playing out to become what we later call disease, and then move it forward to ask, does it arise from dysfunction? And if so, can we modify the environment, because we can't yet modify the genes,

of that individual to create a different outcome called their phenotype? Because within our genotype are multiple phenotypes, right? Do we all agree with that? There are no such things as genes for obesity, genes for autism, genes for heart disease, genes for diabetes. There are susceptibility genes that interrelate

that person's genetic history with their environment that give rise to greater opportunities to express disturbed metabolism that we call histopathology. But there is not a specific gene that we're going to say is the autistic gene or the heart disease gene or the diabetes gene or the bad day gene, right? These are complex arrays of symphonic orchestrated...

phenotypes that emerge from turning on and turning off families of genes based upon the proprio-receptor signaling that comes from the environment through the signaling receptors that ultimately alter cellular function. Now this model that I'm describing, this is paradigm shifting. This is kind of what I call post-genomic view of chronic illness.

And the only way you can understand this, I believe, is through a systems approach. You can't understand it one point on a curve at a time, where you're just analyzing, oh, I know that point. I know everything about its three-dimensional origin on that Cartesian graph, so I understand it.

You can only understand it as a pattern of how that point is connected to other points within the function of the organism. Okay, so as Dr. Minnick pointed out in this beautiful article that she was the principal author of, which I got to tag my name along, on lifestyle medicine,

these are lifestyle-induced chronic illnesses that are complex relationships to how we live, act, think, breathe, eat, and our genes, this point of intersection, the great intersection of life, our book of life, how it responds to the environment in which it's being read, becomes our health or disease patterns.

And so this is a changing paradigm in which the old model, now this is still, unfortunately, still kind of the dominant model, but I call it the model heading to the happy hunting grounds of extinction. And that is a differential diagnosis, which is a reductionistic, taking big things and trying to reduce them down to one thing,

eliminating confounding variables. So you throw out all the stuff that you don't really understand because you don't think it's important. This is like saying, in the human genome, There's a bunch of DNA in there that we don't know what it does. This is 20 years ago. So what was it called? Junk DNA, right?

So we just say, all of that DNA is probably just a relic. We don't know what it is. We're only interested in the DNA. Discover after the Rose Garden description that we had deciphered the book of life, the human genome. We found, oh my word,

all that stuff that we call junk DNA is actually the point of differentiation between us and all other plants and animals. Because if you just look at the genes within our genome, we're 97.6 homologous to the chimpanzee. Too close to comfort for most people. So the difference between us and a chimpanzee isn't the coding genes.

It's the regulatory genes that are located within what? The junk DNA. So it's not junk at all. It is the information processing system. It's the executive centers that regulates how our genes are expressed in response to the environment. That's the big news. That's the major discovery of the Human Genome Project.

And so what the old model does is it directs us down through this reductionistic model to ultimately getting to a definition that becomes the name of what that person has. Oh, so good to know I have systemic lupus erythematosus. Where did it come from and how do I get over it? Well, we're not sure,

but we have symptoms depressing things that will block the immune system so that you won't have to worry about it anymore. But now you can tell people you've got SLE. Right? So this naming and blaming model becomes part of the old example of how we've treated or how we've looked at illness. And then lastly,

I've talked about symptom suppressing medications that are based upon a target receptor interaction of a ligand that then is able to block a message of the body. So that if you uncouple the message, like an anti-inflammatory and antidepressant with SSRIs or anti-H2 blocker for acid production from the stomach or, and we could go down the list, right,

or an inhibitor of angiotensin converting enzyme, all these various drugs are there to effectively uncouple certain messages so that the person goes home feeling, I'm feeling better now. I must be okay. I must be well. But we actually are just on the path to wellness. Maybe we've reduced one component of their illness,

but maybe the central theme of the cause is still present. We've just kind of uncoupled the fire detector a little bit, the smoke detector. So the new model, it looks at the ideological causative factors. It includes all variables. The more information, the better. Now we're in the age of big data.

In the past, we always used to say, I don't know what to do with all that information. Now we say we have ways of digesting information. By the way, using the human brain, which is the better pattern recognition device that's ever been invented, it beats even a computer, the most high-powered supercomputers in terms of pattern recognition.

This opens up new lenses for understanding the etiology of the complex disease of that individual or the dysfunction of that individual. We're then moving to understand how to treat the cause and not the effect. That's the new model. And so the key concepts that emerge out of this are some terms that are new to our language.

like emergence, where an emergence structure arrives in that individual. How they look, act, and feel emerges out of how their genes interact with their environment. That's an emergence structure. The exposome, which is this series of receptors that pick up information from our environment, the exposures that we have to various substances, not just persistent organic pollutants,

but all sorts of other information that we're getting, including radiation from the environment, some of which is non-ionizing radiation, long wavelength microwaves and other things, that we have these receptors that can pick up that information and translate it into gene expression patterns that alters physiological function well before pathology. Then we have epigenetics,

which is these marks that are put on genes that are like the fine-tuning knob of how our body responds to its environment. So the coarse-tuning knob is called selective, I guess we call it Darwinian natural selection, don't we? Really, mutations that are selected for that give benefit over hundreds of thousands of years to a species.

But in the fine-tuning knob that allows us to alter our physiology in response to a rapidly changing environment is called epigenetics, where we put these methyl groups or these phosphorylated groups or these histone-acetylated groups onto our genome that turns on and turns off the ability to express certain messages in response to an immediate environmental change, like famine,

for instance. because we know that second-generation daughters from mothers who went through a famine then end up having different epigenetic marks that alters the way they respond to glucose in their body, and they have different insulin sensitivity and higher risk to type 2 diabetes. So that leads then into nutritional genomics or nutrigenomics,

which is a new term that's kind of a convoluted, connected term that talks about individualized nutrition based upon the genetic connections of the person. Pharmacogenomics, which is there's no such thing as one drug fits all. The age of blockbuster drugs is over. And doctors are now being sued for prescribing a drug, not asking the question,

did the patient have the proper detoxification enzymes for that drug? And if they got an overdose and they didn't ask if they're a 2D9 slow metabolizer, when they give them an SSRI, they can be held medically legally liable for an adverse response that that patient had.

This is a whole new age relative to the way we view pharmacology. And that leads into proteomics and metabolomics and kinomics and lipomics and all these omics. The trilogy of omics, right? And we just keep oming ourselves to greater states of enlightenment. And these omics are that which then tell us how our genes are responding to our

environment through the translation of the message into mRNA, into proteins, into post-translational effects on proteins, ultimately into metabolic patterns, and into our physiology. By the way, I'm doing a self-justification for being a biochemist in case you really were asking what's my hidden agenda here. So what I'm really saying is health is personal.

It's not medicine of the average. In fact, Alex used a real nice example of Roger Williams. The first time I met him was 1974. He and Linus Pauling and Eva Helen Pauling were together at the inaugural meeting of the American Academy of Preventive Medicine, which was in Houston in 1974.

I was, believe it or not, a young guy at that meeting. And I got a photograph, one of my classics, of them together in the foyer of that meeting. And Roger Williams said, nutrition is for real people. Statistical humans are of little interest. And boy, that just was like raised on my frontal lobes of my brain.

I've remembered that so clearly ever since then, because I recognize that we spend a lot of time studying statistical humans, but we never see one in practice. Everyone comes in as not, like doesn't fit into the midsection of the Gaussian curve, because if they did, they probably wouldn't be visiting us.

Most people don't wake up in the morning and say, I feel so great. I'm going to my practitioner to find out why. You know, it's not a standard operating procedure. They come because they're on the bell shape. They're outliers in the curve. So they, you know, who protects the outliers? Well, that's this field, right?

Looking at functional or dysfunctional components. It's personal. So we're looking at a global shift in personalization, and that's why we put together this kind of interrelationship between the Institute for Functional Medicine and the functional medicine model addressing the underlying cause of disease using this systems-oriented approach. what we now call personalized lifestyle medicine.

And so people say, well, why do we have a new term, Jeff? Why don't we just keep functional medicine and raise the banner on functional medicine? I think functional medicine is a great term for an operating system as to how health care should deliver services to chronically ill people.

But it's not a term that is warm and fuzzy for most people on the street. If you bring up functional medicine, that's not something immediately I get. They'll get it as you go through, like if you're in an elevator speech, you need about 100 floors in the elevator to really describe it.

We felt that maybe there was some docking station for health-conscious consumers that would get them into the system by reducing kind of that first language barrier. So we thought everybody has a lifestyle. We understand that personalization is becoming a major theme with this post-genomic era that we're living in.

And that there is a form of healthcare delivering that personalized healthcare that is the functional medicine operating system. So let's go with a consumer facing and call it personalized lifestyle healthcare or personalized lifestyle medicine. And then we'll anneal those health conscious consumers that come in through personalized lifestyle medicine concepts on social media, crowdsourcing,

and getting this kind of as a as a banner that we can get to legislators and regulators and policymakers and reimbursement people. And then we bring the operating system of functional medicine in as the way that practitioners are trained. So that's our kind of big strategic model.

Now, it hasn't been proven yet to be successful, but that's what we're working on. So we formed this Personalized Lifestyle Medicine Institute, of which Deanna is the Vice President of Education. And it's a small group. There's just eight of us, but we are changing the world. That's our belief, right?

Every day is a chance to make a contribution to changing the world as it relates to the perception of health and disease. I do have a book coming out in April that's kind of my... I guess you would call it my tour de force book. It's probably going to be about 400 pages,

which is the review of the history of this whole emergence of personalized lifestyle health care and functional medicine, and actually will be the first book, I think, with functional medicine in the title to the direct consumer. I have a really good publisher who has been very motivated to put a lot of public relations background behind this book.

So I'm hopeful that it will be another contribution to the voice of what we're trying to get people to understand. That health is much more in their control than they really recognize. that they're not a victim, they can be an ally to their own health, they can have self-efficacy,

and they can work with the right kind of provider as a team member, so they need to be seeking out a functional medicine provider to serve their health needs as they move forward. So that's the title, the working title of the book, by the way, is called Disease Delusion, because as I said,

I think disease is a delusion. I think it's an artifice of what you need to go below that to ask where did it come from. So this is all around the trajectory of disease and the role of how personalized lifestyle medicine plays a role. And you've all seen this,

and I bet you use this in your patient education, this progression that disease doesn't come as a bump in the night. It's a progression over time, generally, of changing function until a person crosses that magic line, which the normal exposures to things in life now triggers a series of responses that we then call a disease.

It is severe enough. with severity, duration, and frequency that a person seeks out the care of some kind of a tertiary care provider to serve their needs to manage it. But it's actually gone way before that. And people just don't have heart attacks on a Monday morning after a vacation as a bump in the night.

If you ask the right questions, you'll get different answers. And this is all about learning how to ask the right questions. When people say, what's the clinical algorithm that delivers functional medicine? I say, it's not about algorithms. It's not about treatment protocols. It's about a way of thinking. It's a way of thinking.

If you ask the right questions and you're trained to know what questions to ask, you will come up with answers you never even thought you knew. That's the concept. You need to have a fertile soil that incubates the ability to have your mind explore the right questions so that then that narrative you have with the patient,

that's their life story, arrives at this discovery moment that gives you both the chance to manage their cause of the disease rather than the effect. So that's our personalized lifestyle medicine. Our mission is to transform healthcare through this conceptual philosophy, to be global leaders in the promotion of this. And our website, as you probably know, Dr.

Minnick was the principal author in this recent article, which we're very surprised to learn was the first time in the medical literature that we can find the term personalized lifestyle medicine was used. So if you do a Medline search or a Google search, you'll see us being hit first, which was quite surprising.

So it's very infrequent in your life that you can own a term. So we're basically, we don't have to do what we do with functional medicine here, which is to reinvent it. So that's what we are all about. I want to tell you once again how much I appreciate your honor, your acknowledgement.

I feel like I'm a soldier in the army of change and I think we're doing some extraordinary work and it's really all because of you. Thank you so much.

Alright, we'll see if we can switch over to a different mic. I think we're good, yeah. I'm gonna turn this one off if possible. See if we can avoid a little feedback.

Only the 3 footnotes cited above are provided below

Listen to this episode with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to INFLAMMATION MASTERY clinical protocols InflammationMastery.com to listen to this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.

![CONFERENCE VIDEO Integrating Functional and Naturopathic Medicine (F.I.N.D.S.E.X.® Protocol) into Medical Practice for Common Primary Care and Specialty Conditions [2020, Moscow]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1300,h_650,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-video.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fvideo_upload%2Fpost%2F152107091%2Fa8110bd8-2b8c-4b8d-9bbb-fef2cf697b89%2Ftranscoded-00001.png)